Bringing Clarity and Order to the Climate Adaptation Toolkit

Date

Climate adaptation science has matured rapidly over the past two decades. In that time, scientists, agencies and practitioners have developed an impressive array of planning processes and guides, decision tools and conceptual models. From scenario planning to response modeling, from adaptation menus to the resist-accept-direct (RAD) framework, the toolbox has expanded in powerful ways.

But with such a growth has also come confusion.

Many practitioners find themselves asking: How do all these resources fit together? Are they competing or complementary? When should one be used over another? And how do we explain this to partners?

A recent NC CASC webinar addressed this issue head-on by offering a simple but important idea: it may be time for the field of climate adaptation to move from divergence toward convergence.

From Expansion to Clarity

Climate change has fundamentally altered the context for natural resource management. Agencies were built on assumptions of ecological stationarity, the belief that historical patterns and baselines provide a relatively stable guide for the future. Today, non-stationarity is the norm. Ecosystems are shifting, disturbance regimes are intensifying, and historical conditions are no longer reliable guides to the future.

In response, the adaptation community has innovated. We now have robust processes for climate adaptation planning and tools for their implementation, including scenario planning, vulnerability assessment, decision analysis and more. This proliferation of processes and tools is a sign of progress. It reflects years of science application, creativity, and interdisciplinary work.

Yet this diversity can also feel overwhelming. Circular diagrams abound. Terminology overlaps. Concepts blur. Even in the scientific literature, terms like “approach,” “process,” and “tool” are sometimes used interchangeably.

The webinar argued that greater clarity is not about limiting innovation, it’s about making innovation usable.

Distinguishing Approaches, Processes, and Tools

The presentation offered a clear distinction among three core concepts:

Approaches are broad guiding philosophies or structures. They provide fundamental principles and concepts about how adaptation should be pursued. Climate-Smart Conservation, developed by a broad set of organizations, is an example of an approach that provides a forward-looking philosophy and principles for managing resources in an era of non-stationarity.

Planning processes are structured sequences of steps used to develop and implement adaptation plans (e.g., The Adaptation Workbook ). These often include steps like defining current goals and objectives, assessing vulnerability, critically evaluating current goals and objectives, identifying strategies, evaluating tradeoffs, implementing actions and monitoring outcomes.

Tools are specific methods or instruments used within a process. These might include scenario planning, structured decision-making (SDM), the RAD framework, or adaptation menus.

This distinction matters. Many disagreements in adaptation practice arise not from substantive differences, but from talking past one another by using different terms for different layers of the same system.

When understood properly, tools are not competing ideologies. They are components embedded within broader planning processes, which in turn operate within overarching approaches. Once that hierarchy becomes clear, the toolkit feels less like a jumble and more like a coordinated system.

The webinar showcased a generalized adaptation planning process to help organize an increasingly complex landscape of approaches and tools. This figure (from Miller et al. 2025) illustrates a full planning cycle—from scoping and vulnerability assessment through strategy selection, implementation, and evaluation—and shows where specific tools can be embedded. SBDA = Scenario-Based Decision Analysis; SDM = Structured Decision Making; CCSP = Climate Change Scenario Planning; CCVA = climate change vulnerability assessment; RAD = Resist–Accept–Direct; RRT = Resistance–Resilience–Transformation

The “Groan Zone” and Field Maturity

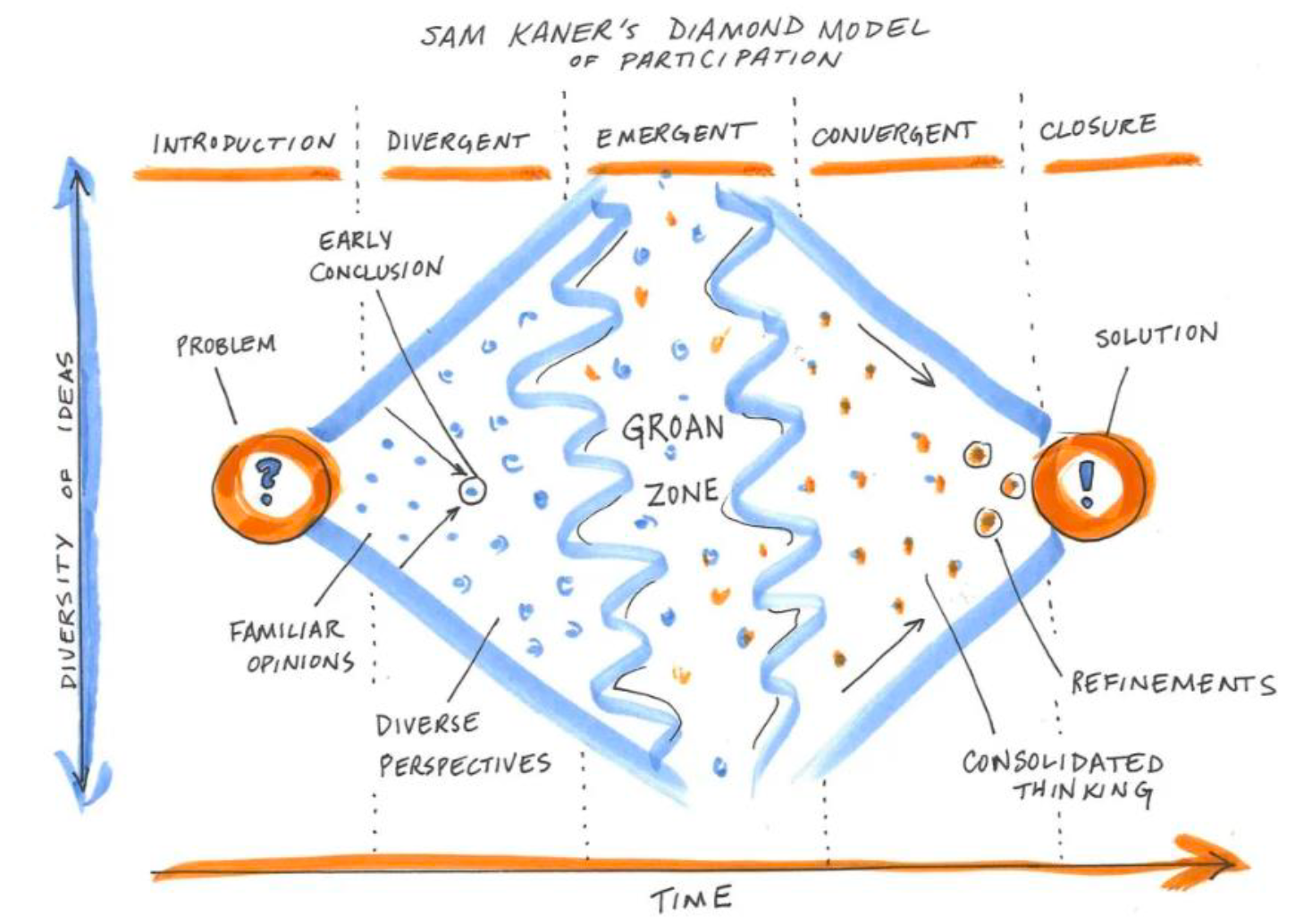

The presenters drew on a familiar participatory model that describes how groups move from divergence to convergence. In early stages, ideas proliferate. Perspectives multiply. Creativity flourishes over time but so does confusion. This leads us to what is called the “groan zone.”

Climate adaptation may now be moving out of its groan zone.

The field has experimented widely. Now, there are signs of coalescence and an opportunity to consolidate and to articulate how these processes align, where they differ, and how key tools can be used in complementary ways. This does not mean arriving at a single “correct” adaptation method. Instead, it means developing shared language and shared structure so practitioners can coordinate across agencies, jurisdictions, and disciplines.

That coordination is especially critical for landscape-scale challenges that transcend administrative boundaries.

Figure credit: Kappel, C. (2019, May 28). Collaboration: From groan zone to growth zone. https://i2insights.org/2019/05/28/collaboration-groan-zone/. Adapted from: Kaner, S. (2014). Facilitator's guide to participatory decision-making. John Wiley & Sons

Revisiting Goals in a Non-Stationary World

A recurring theme in both the presentation and discussion was the need to reconsider management goals under climate change.

One proposed step in the adaptation process is to explicitly review and potentially revise conservation goals before identifying strategies. Climate change may render some historical objectives unattainable or socially undesirable. However, participants in the discussion emphasized that goal evaluation and revision is often iterative. In practice, managers may explore adaptation strategies first, then revisit goals in light of what is feasible, socially acceptable, and ecologically viable. The back-and-forth between goals and strategies is not a flaw in the process, it is a reflection of adaptive learning.

Further, iteration is central to successful climate adaptation processes. There is no single pass through the cycle. Monitoring, evaluation, and revision are critical pieces of the adaptive management approach.

A Shared Vision for Climate-Informed Stewardship

At its core, the webinar conveyed a hopeful message.

The adaptation field has generated remarkable intellectual capital. What is needed now is greater coherence and a shared vision of climate-informed resource stewardship that helps practitioners navigate complexity rather than drown in it.

By clarifying terminology, organizing tools within processes, and embracing iteration, the adaptation community can move toward more coordinated and effective action. The goal is not simplification for its own sake, but accessibility so that managers, scientists, and partners can work from a common foundation.

In a rapidly changing world, clarity is not a luxury. It is a prerequisite for action.

Publication: Miller, B.W., Schuurman, G.W., Carr, W., Lawrence, D.J., Thurman, L.L., Bamzai‐Dodson, A., Brandt, L.A., Crausbay, S.D., Cross, M.S., Eaton, M.J. and Janowiak, M.K., 2025. Toward a shared vision for climate‐informed resource stewardship. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 23(10), p.e70005. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.70005