Developing an Adaptation Menu for the Sagebrush Biome

by Elizabeth Woolner

Imagine you could be handed a printed menu, but instead of viewing what food or drinks are available, you could read about the various ways to save an ecosystem. Or, imagine that ecosystem “doctors” could have a guide available to them that helps determine what course of action to take; what “treatments” are available for the land. This, in part, is what our sagebrush science synthesis team began work on this summer through the Rapid Climate Assessment Program (RCAP).

What is the sagebrush biome?

“Thirty minutes after sunrise, mid-May in Oregon sagebrush country and the earth is an eerie electric shock of green. The vegetation seems to glow more the way metal does when white-hot, radiating beyond color into pure light.” - Cahill, 2024

“The Sagebrush Sea, a vast landscape of broad valleys, stark mountains, and endless plains with a hazy blue green canopy of sagebrush out to the horizon, is evaporating.” - Cahill, 2022

Sometimes called the “Sagebrush Sea,” the western US is home to a shrub-dominated biome known as sagebrush steppe. Anchored by the presence of a variety of sagebrush species, this landscape covers roughly 133 million square miles - about the size of New Mexico - though, historically, it stretched across an area nearly as large as Texas (239 million square miles). Ranging all the way from California to the very edge of the Dakotas, it’s a water-scarce landscape that sometimes looks more like a desert than a shrubland. Ranching is a primary human use of these landscapes, and cattle are a common sight among the shrubs. You may have heard of the sagegrouse, a politically-notable bird species that calls this landscape home, but the grouse is only one of many unique animal and plant species hosted by the sage. A relatively large proportion of this landscape is public land, managed by state and federal agencies.

As may feel standard for our day and age, the threats that the sagebrush sea faces are many and vary across its extensive range. In the North Central region, we are most concerned with the increasing presence of invasive grasses and their connections to fire, conversion of sagebrush to croplands or urban infrastructure, and the transformation of landscapes due to climate change. Our sagebrush lands - generally located at higher elevation and higher latitude - hold more “core” sagebrush areas. As a result, crucial questions for the management of these “core” areas are key for the biome at large: What impacts are we likely to see in the future? And what lessons can we learn from the Great Basin systems that have already suffered significant sagebrush losses? One of the NC CASC's goals is to support the variety of land management organizations working in the sagebrush sea to improve the biome’s chances of surviving and thriving under a changing climate.

What is land management, exactly? Fundamentally, land management is any deliberate action taken to “manage” the resources and entities on a particular piece of land, such as the animals, plants, soils, water, air, and other systems that the land contains. It involves aligning what is physically possible on the ground with our values and long-term visions for the land itself.

Though the phrase is often associated with public agency decisions to maintain wildlife, vegetation, and other ecological systems “in perpetuity,” land management includes both public and private actors. These can include individual landowners, corporations, or non-governmental organizations like The Nature Conservancy. It’s a vast field, with as diverse a community of practice as there are landscapes on the ground. Agencies alone employ a variety of personnel including long-term strategic planners, scientists, managers, educators, volunteer coordinators, law enforcement, seasonal workers, and support staff. The kinds of decisions this community makes ranges all the way from long-term climate adaptation planning to deciding whether to put in additional restrooms at a particular trailhead.

Land management is a critical aspect of our response to a changing environment, and it combines insights from natural science alongside our values and visions for the future. How can scientists support this effort to adapt? How can we help to link research and evidence with a holistic understanding of the sagebrush landscape, and provide guidance in an accessible way? One way is to create an adaptation menu.

What is an adaptation menu?

An adaptation menu is essentially a nested list – a structured catalog of potential actions to help sustain healthy ecosystems and meet management goals under climate change. It bridges big ideas like “community engagement” or “reducing disturbance” with specific, actionable steps a manager can take. It also demonstrates the adaptation intention of management activities, helping managers draw pictures between what they are doing on the ground and how it relates to climate adaptation more broadly.

The name “menu” is intentional. Imagine each section of the sagebrush menu like a restaurant layout. You might choose a main dish and drink but skip the appetizer. Within each section, there are multiple options that may work well together or not, depending on your “taste” – in this case, the site’s conditions and management context. What works in one area might be counterproductive in another.

Here are some adaptation menu definitions, taken from the Forest Adaptation Menu, using a medical analogy.

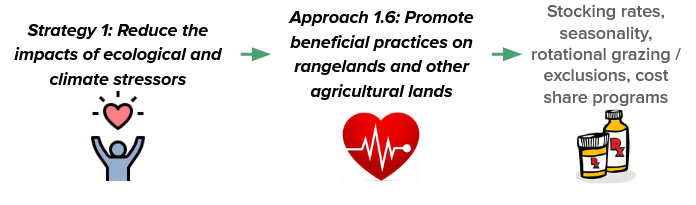

Figure 1: Examples of a nested strategy, approach, and sample tactics. The icons represent what each category translates to in a medical analogy, described below.

Strategies: Broad adaptation responses that consider ecological conditions and overarching management goals

Strategies are the highest distinct level and are broad responses that consider both conditions and overarching management goals. If we consider a medical analogy, imagine a doctor has a patient presenting a set of problematic symptoms. The “strategy” in this case may be broad goals like “improve quality of life” or “mitigate the most troubling symptoms”.

Approaches: More detailed adaptation responses with consideration of site conditions and management objectives

Approaches are connectors - they link broad objectives and recommendations with a more specific context. For example, pursuing beneficial agricultural practices may not be helpful on every sagebrush site or parcel. Using the medical analogy, this may be likened to “lessen cardiac stress” or “improve respiration efficiency”.

Tactics: Prescriptive actions designed for specific site conditions and management objectives

Tactics move towards specific actions or activities that are chosen by managers. We liken these to specific medications or procedures that a doctor could recommend for a patient. Prescriptive means providing recommendations or guides for how things should be done (as opposed to descriptive, which characterizes what is).

In many cases, there even appeared to be a finer level than tactics, which is the actual “how” of management activities on the landscape, or the actions to take. Following the analogy, this level is similar to differences in dosage, time of application, or other specifics that doctors determine for their patient as part of developing a treatment plan.

Reviewing the literature on effective sagebrush management

Our menu began with a literature review - searching, reading, and synthesizing scientific papers on sagebrush management. I reviewed over sixty peer-reviewed articles, focusing on outcomes and recommendations, and documented them in a spreadsheet.

From there, I went through several rounds of organization and synthesis, adding insights and outcomes into a living, collaborative document. We took a “more-is-more” approach, gathering additional feedback for later refinement. We also conducted seven stakeholder interviews to “ground-truth” the findings and add practical perspectives.

The goal is to eventually present the menu as an interactive digital tool, where each approach and tactic is tagged by topic (e.g., “fire,” “grazing,” “disturbance,” “social support”). Users could filter and quickly find the guidance most relevant to their site or objectives, similar to well-designed websites or apps that use tag-based navigation.

The Draft Menu

Despite the swelling scope and sophistication of our knowledge, the toolkit at our disposal for restoration remains spare and simple. We can spray weeds, plant seeds, fix streams, and cut trees. - Cahill, 2024

One aspect of the menu is taking a relatively simple set of tools, as described above, and exploring the context in which they might be applied. Each likely deserves its own report with guidance for use under different circumstances. Ultimately, we hope to link these tools, their applications, and guidance with broader ecological and social justifications for their use. Essentially, we will provide managers with guidance and rationale for how their on-the-ground activities matter to overall climate adaptation and sagebrush conservation.

As of the time of writing, there are eight proposed strategies (details omitted for future publication purposes). Each strategy contains at least two approaches, and between one and thirty different tactics associated with the approaches. An example includes Strategy 1 (subject to change):

Overall, we’re pleased with the increased emphasis in the menu on social and organizational aspects of management compared to other menus; this is in part due to the expertise of the grad student cohort this summer, including the work of Lauren Lee Barrett on Strategy 8. Furthermore, the integration of tactics throughout the development process anchors big ideas to on-the-ground activities and increases the focus on management effectiveness.

Where are we going from here?

How big is big enough to matter but small enough to act? - Cahill, 2024

A key challenge of developing this menu were differences in scale between different strategies, approaches, and tactics. Some ideas mentioned at the same conceptual level can only be applied at dramatically different spatial or timescales, which begs the question of whether they should be organized into the same category. There are different on-the-ground management implications, like what actions are accessible or useful for managers, depending on how we arrange these ideas. We also need more literature in specific areas, including integrating Indigenous knowledge and other cultural perspectives into the menu’s literature base.

As I continue this work into the fall, our team is focused on editing, refining language, and ensuring clarity and usability. The Sagebrush Adaptation Menu is a living document, one that will evolve through feedback from our working group and partners. Taking all that feedback and weaving it back in won’t be easy, but the goal remains clear: to produce the best possible tool for those caring for the Sagebrush Sea.

About the Author: Elizabeth Woolner is a PhD student working at the intersection between research, the public, and land management communities. Her mixed methods, multi-disciplinary research focuses on environmental values, measurement, and understanding the role of social factors in decision-making around changing landscapes. Elizabeth was born and raised in northern Colorado. Her love for the area inspires her work on local and regional socio-ecological systems.

References

Cahill, M., 2024, There is No Hope Without Change: A Perspective on How We Conserve the Sagebrush Biome, Rangeland Ecology & Management, 97, 209-214.

Cahill, M., 2022, The range has changed: My viewpoint on living in the Sagebrush Sea in the new normals of invasive and wildfire, Rangelands, 44(3), 242-247.

Photo: John Bradford, USGS