Ecological Scenarios for Climate-Smart Management in the American West

Date

As climate change reshapes landscapes across the North American West, land managers are facing an increasingly complex set of challenges. Rising temperatures, shifting precipitation patterns, and intensifying wildfires are altering the ecological dynamics of forests, grasslands, and rangelands. How do you prepare for a future that’s not only novel but also one that cannot be accurately predicted?

New research from the North Central Climate Adaptation Science Center (NC CASC) at the University of Colorado Boulder offers a way forward. Led by NC CASC ecologist Kyra Clark-Wolf and climate scientist Imtiaz Rangwala, as well as USGS collaborators, Brian Miller, Helen Sofaer, and Wynne Moss, the study introduces a powerful framework for navigating ecological uncertainty: developing plausible, science-informed scenarios that can guide decision-making even when the path ahead is uncertain.

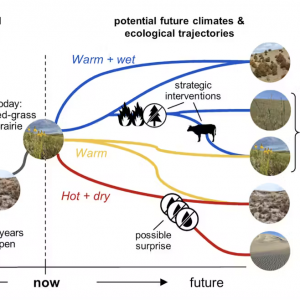

Published in Ecosphere, the open-access study emphasizes the value of “ecological scenarios”, or narratives that envision a range of potential futures based on diverse climate trajectories and uncertainty in ecological responses. These scenarios are not predictions but structured storylines of the future informed by modeling and historical evidence, to support long-term planning and strategic thinking in the face of deep uncertainty. “Ecological scenarios don’t eliminate uncertainty,” said Clark-Wolf, “but they can help to navigate it more effectively by identifying strategic actions to manage forests and other ecosystems.”

The study was co-produced with input from scientists and practitioners whose work emphasizes climate change adaptation in natural resource management, including from federal agencies across the North Central region of the U.S., from the Rocky Mountains to the Great Plains. These practitioners brought decades of on-the-ground experience to the table, helping researchers understand the real-world needs of those managing vast and diverse public lands. The approach is rooted in the principle of “actionable science”, a hallmark of the national network of Climate Adaptation Science Centers, which emphasizes research that is both scientifically rigorous and directly usable by decision-makers.

Clark-Wolf et al.’s framework focuses on ecological uncertainty - that is, the uncertainty not just about how the climate will change, but about how ecosystems themselves will respond to it. For example, will a forest transition gradually to grassland? Will an invasive species take over after a fire? Will tree regeneration fail under prolonged drought? These are not questions with single answers.

The development of ecological scenarios is guided by three major principles:

Embracing Ecological Uncertainty: Instead of relying on a single ecological outcome per climate scenario, explore multiple plausible ecological pathways. This approach helps identify shared vulnerabilities and design management strategies that are resilient across a range of futures.

Thinking in Trajectories: Look beyond future endpoints and focus on the dynamic processes shaping ecological change. Understanding trajectories, like how disturbance sequences influence ecological transitions, can reveal opportunities for effective management intervention.

Preparing for Surprises: Plan for rare but high-impact ecological surprises, such as unexpected pest outbreaks during drought. Anticipating these extremes enhances preparedness and supports agile, responsive management.

This approach, the authors argue, is especially important for climate adaptation in ecosystems that are already changing rapidly. For example, western U.S. forests have experienced widespread tree mortality from beetle outbreaks, fire, and drought. Managers may not know which species will dominate in the coming decades, but by envisioning several divergent futures, they can identify actions that are robust across all of them.

One key takeaway from this work is that scenario planning is not just about data; it’s about people. Ecological scenarios become most useful when embedded in a participatory process that includes dialogue, trust, and creativity. In their scenario planning experiences, Clark-Wolf’s collaborators have found that the development of ecological scenarios sparked rich conversations among managers, helping them confront difficult trade-offs and test the resilience of their strategies. Across past applications, the act of developing and discussing scenarios led to new insights, and, in some cases, new management priorities. By working alongside land managers, the NC CASC team ensures that the resulting scenarios incorporate not just climate science, but also the social, political, and ecological realities that shape management decisions.

The need for scenario-based thinking is becoming more urgent as the pace and magnitude of climate change accelerates. According to recent projections, many ecosystems in the North Central U.S. could experience climate conditions outside the historical range of variability over centuries, within just a few decades instead. These novel climates will challenge assumptions about restoration, conservation, and land use, and may require a shift from preserving the past to navigating an unfamiliar future. This study offers new insights for how to do that effectively. By investing in ecological modeling, building partnerships, and engaging land managers in scenario exploration, agencies can prepare not just for one future, but for many. This work also complements larger-scale efforts such as the National Climate Assessment’s adaptation chapters, which increasingly emphasize the role of uncertainty in shaping resilience strategies.

The revolution in accessible climate model projections over the past decade has fundamentally empowered resource managers to explore future climate scenarios. However, a critical gap remains: managers today lack similar, ready access to ecological model projections and decision-support tools needed to anticipate how ecosystems might respond. To bridge this gap, Clark-Wolf et al. recognise that the ecological modeling community and data providers must urgently prioritize the development and delivery of ecological projections that capture critical uncertainties and user-friendly decision-support tools. Providing these resources is essential for crafting actionable, robust ecological scenarios.

In a time when uncertainty can feel paralyzing, this research offers a different message: that embracing uncertainty can be empowering. That by imagining many futures, we can better prepare for whatever comes next. As the climate continues to change, the forests, grasslands, and rangelands of the American West will not look the same. But with the right tools and partnerships, land managers don’t have to navigate that future alone, or blindly. With a better understanding of potential scenarios for ecological change, they can face the future not with fear, but with foresight and preparedness.

Image: T. Walz, M. Lavin, C. Helzer, O. Richmond, NPS, CC BY